Gastropod looks at food through the lens of science and history.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Historic jelly molds recreated by Ivan Day, from his website.

Historic jelly molds recreated by Ivan Day, from his website.

Ivan Day is a social historian with a serious jelly mold habit. "I've got hundreds—I don't know. I may have thousands," he told Gastropod. As part of his research, Day has painstakingly recreated many of the most glorious desserts from what he calls the "Golden Age of Jelly," in 1700s and 1800s Britain. Before then, jelly had largely been a savory affair, a textural side-effect resulting from melting the collagen in animal bones and cartilage during cooking and then cooling the dish, which allowed the melted collagen to gel. But, with the increasing availability of sugar and the technology to produce affordable stoneware and metal molds, an elaborate molded jelly became the essential culmination of any upper-class banquet—a pre-Instagram Instagrammable food par excellence.

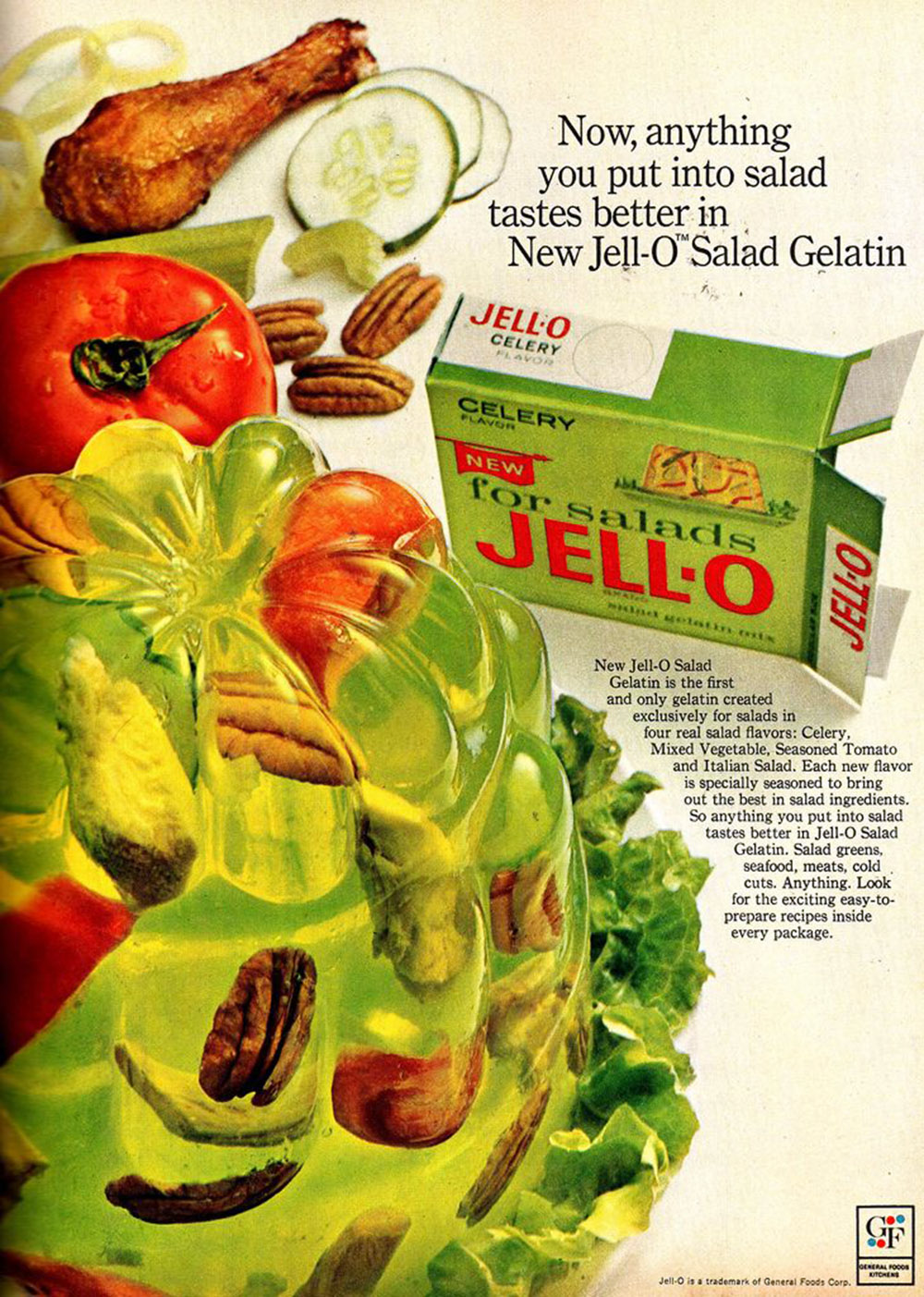

That all changed in the twentieth century, as jelly reinvented itself as Jell-O. Following the invention of powdered gelatin by a man better known for laying the first telegraph cables under the Atlantic and building the first practical steam locomotive made in America, Jell-O became the country's most popular dessert. "Jell-O felt like this food of the future, that could really coincide with our collective fixation with science and progress," Allie Rowbottom, a Jell-O heiress and author of a new memoir, Jell-O Girls, explained. She said that, by the 1950s, "you'd be hard-pressed to go to a potluck anywhere in America and not find a Jell-O mold of some sort."

That all changed in the twentieth century, as jelly reinvented itself as Jell-O. Following the invention of powdered gelatin by a man better known for laying the first telegraph cables under the Atlantic and building the first practical steam locomotive made in America, Jell-O became the country's most popular dessert. "Jell-O felt like this food of the future, that could really coincide with our collective fixation with science and progress," Allie Rowbottom, a Jell-O heiress and author of a new memoir, Jell-O Girls, explained. She said that, by the 1950s, "you'd be hard-pressed to go to a potluck anywhere in America and not find a Jell-O mold of some sort."

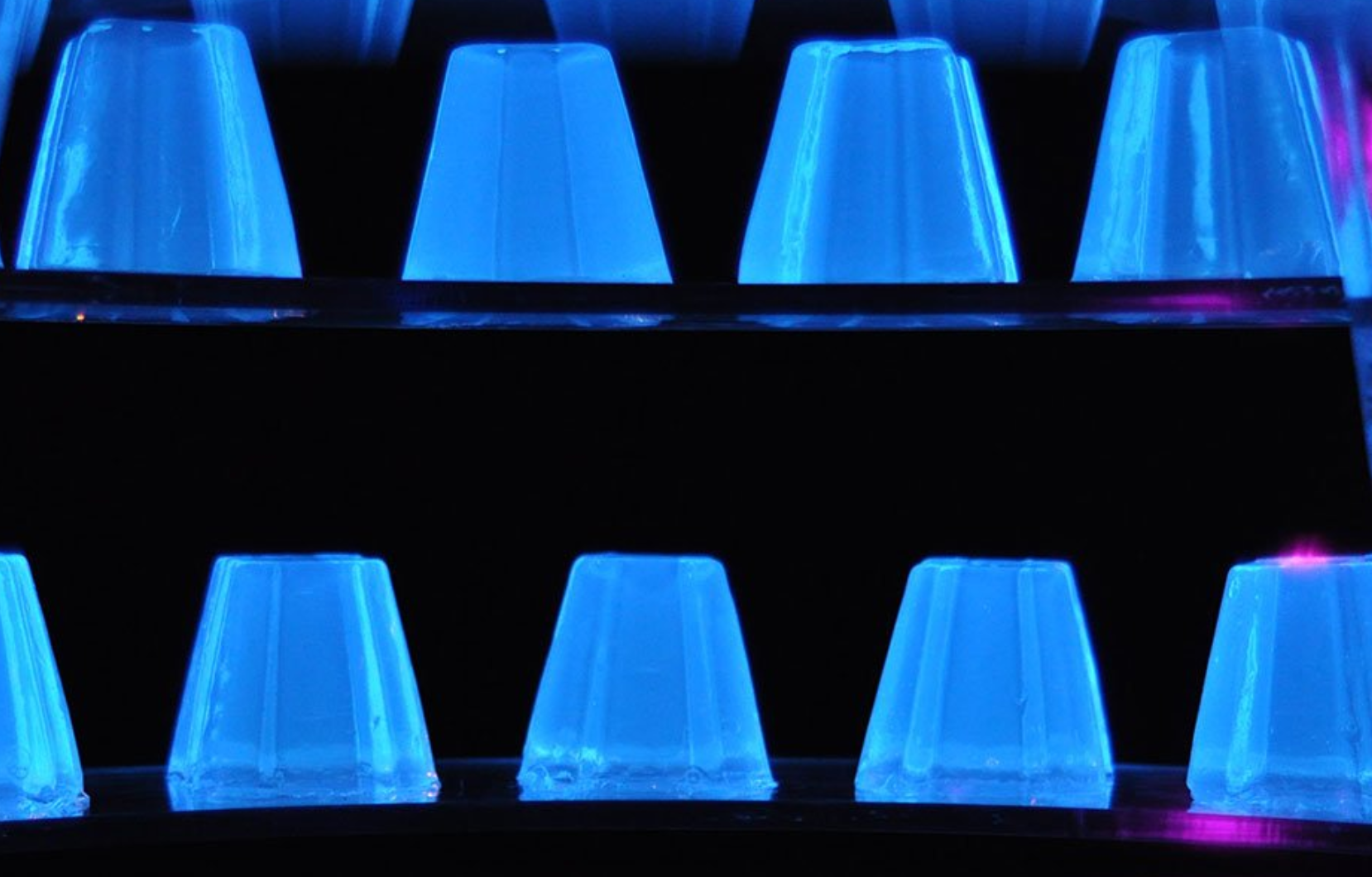

Bompas & Parr's glow-in-the-dark jelly.

Bompas & Parr's glow-in-the-dark jelly.

Thai agar jelly mold; photo via Rawewon Sutichavengkul.

Thai agar jelly mold; photo via Rawewon Sutichavengkul.

But the second half of the twentieth-century was not kind to Jell-O, despite Bill Cosby's best efforts as the company's former spokesperson. Today, most jelly is eaten by the under-ten set, hospital inpatients, or Weight Watchers members looking for a zero-point dessert. Unless, of course, you're in Thailand, where Gastropod listener and agar factory owner Rawewon Sutichavengkul told us that elaborate agar jelly molds are popular among adults and children alike. Or South London, where British food magicians Sam Bompas and Harry Parr have been leading a jelly revival, featuring glow-in-the-dark jellies, holographic jellies, and jellies so big you could float a steamship on them. Listen to this episode for all these stories and more, including the forgotten first lady of microbiology, the unusual uses of gelling agents in today's processed food, and the surprising connection between Jell-O and Ellis Island.

Entries into Bompas & Parr's Architectural Jelly Banquet.

In 2007, Sam Bompas and Harry Parr went into business as jelly-mongers. Their first major public event was an architectural jelly banquet, a competition held as part of the 2008 London Festival of Architecture. Bompas & Parr challenged the world's leading architects to submit their own designs to be made into jelly molds: the resulting event featured more than a thousand jellies, many of which ended up being thrown as the jelly viewing and awards ceremony descended into what Bompas called "a jelly party-riot." In the intervening decade, they've created many more jellies, as well as a bar filled with aerosolized gin and tonic, a building flooded with punch, and an ice-cream exhibition, currently on display in London. Should you wish to participate in the jelly revival, their book, Jelly, will provide an excellent guide.

55,000 litres of lime green jelly surrounding Isambard Kingdom Brunel's steamship, the SS Great Britain, by Bompas & Parr.

Ivan Day is a social historian specializing in the history of food. He also runs unique practical courses on period cookery, including jelly. You can learn more at his website, which is also full of fabulous photos.

Kantha Shelke is a food scientist and founder of Corvus Blue, a food research and consulting firm, as well as a visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University. She previously appeared on our episode Who Faked My Cheese?

In her new book, Jell-O Girls, Allie Rowbottom tells the story of her family's involvement in the Jell-O business, as well as their subsequent riches and struggles.

Gastropod listener and supporter Rawewon Sutichavengkul's family business is agar jelly, which is used to make fabulous desserts in her native Thailand, as well as provide the basis for culturing microbes in Petri dishes.

Seaweed gets washed, bleached, boiled, and the resulting gel skimmed off. Photos from Rawewon Sutichavengkul.

Click here for a transcript of the show. Please note that the transcript is provided as a courtesy and may contain errors