Gastropod looks at food through the lens of science and history.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

But cheese is not just a treat for the palate: its discovery changed the course of Western civilization, and, today, cheese rinds are helping scientists conduct cutting-edge research into microbial ecology. In this episode of Gastropod, we investigate cheese in all stinking glory, from ancient Mesopotamia to medieval France, from the origins of cheese factories and Velveeta to the growing artisanal cheese movement in the U.S. Along the way, we search for the answer to a surprisingly complex question: what is cheese? Join us as we bust cheese myths, solve cheese mysteries, and put together the ultimate cheese plate.

This is the story you'll often hear about how humans discovered cheese: one hot day nine thousand years ago, a nomad was on his travels, and brought along some milk in an animal stomach—a sort of proto-thermos—to have something to drink at the end of the day. But when he arrived, he discovered that the rennet in the stomach lining had curdled the milk, creating the first cheese. But there’s a major problem with that story, as University of Vermont cheese scientist and historian Paul Kindstedt told Gastropod: the nomads living in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East in 7000 B.C. would have been lactose-intolerant. A nomad on the road wouldn't have wanted to drink milk; it would have left him in severe gastro-intestinal distress.

Kindstedt, author of the book Cheese and Culture, explained that about a thousand years before traces of cheese-making show up in the archaeological record, humans began growing crops. Those early fields of wheat and other grains attracted local wild sheep and goats, which provide milk for their young. Human babies are also perfectly adapted for milk. Early humans quickly made the connection and began dairying—but for the first thousand years, toddlers and babies were the only ones consuming the milk. Human adults were uniformly lactose-intolerant, says Kindstedt. What's more, he told us that “we know from some exciting archaeo-genetic and genomic modeling that the capacity to tolerate lactose into adulthood didn’t develop until about 5500 BC”—which is at least a thousand years after the development of cheese.

The real dawn of cheese came about 8,500 years ago, with two simultaneous developments in human history. First, by then, over-intensive agricultural practices had depleted the soil, leading to the first human-created environmental disaster. As a result, Neolithic humans began herding goats and sheep more intensely, as those animals could survive on marginal lands unfit for crops. And secondly, humans invented pottery: the original practical milk-collection containers.

In the warm environment of the Fertile Crescent region, Kinstedt explained, any milk not used immediately and instead left to stand in those newly invented containers "would have very quickly, in a matter of hours, coagulated [due to the heat and the natural lactic acid bacteria in the milk]. And at some point, probably some adventurous adult tried some of the solid material and found that they could tolerate it a lot more of it than they could milk.” That's because about 80 percent of the lactose drains off with the whey, leaving a digestible and, likely, rather delicious fresh cheese.

With the discovery of cheese, suddenly those early humans could add dairy to their diets. Cheese made an entirely new source of nutrients and calories available for adults, and, as a result, dairying took off in a major way. What this meant, says Kindstedt, is that “children and newborns would be exposed to milk frequently, which ultimately through random mutations selected for children who could tolerate lactose later into adulthood.”

In a very short time, at least in terms of human evolution—perhaps only a few thousand years—that mutation spread throughout the population of the Fertile Crescent. As those herders migrated to Europe and beyond, they carried this genetic mutation with them. According to Kindstedt, “It’s an absolutely stunning example of a genetic selection occurring in an unbelievably short period of time in human development. It’s really a wonder of the world, and it changed Western civilization forever.”

In lieu of an actual time machine, Gastropod has another trick for listeners who want to know what cheese tasted like 9,000 years ago: head to the local grocery store and pick up some ricotta or goat’s milk chevre. These cheeses are coagulated using heat and acid, rather than rennet, in much the same way as the very first cheeses. Based on the archaeological evidence of Neolithic pottery containers found in the Fertile Crescent, those early cheeses would have been made from goat’s or sheep’s milk, meaning that they likely would have been somewhat funkier than cow’s milk ricotta, and perhaps of a looser, wetter consistency, more like cottage cheese.

“It would have had a tart, clean flavor,” says Kindstedt, “and it would have been even softer than the cheese you buy at the cheese shop. It would have been a tart, clean, acidic, very moist cheese.”

So, the next time you're eating a ricotta lasagne or cheesecake, just think: you're tasting something very similar to the cheese that gave ancient humans a dietary edge, nearly 9,000 years ago.

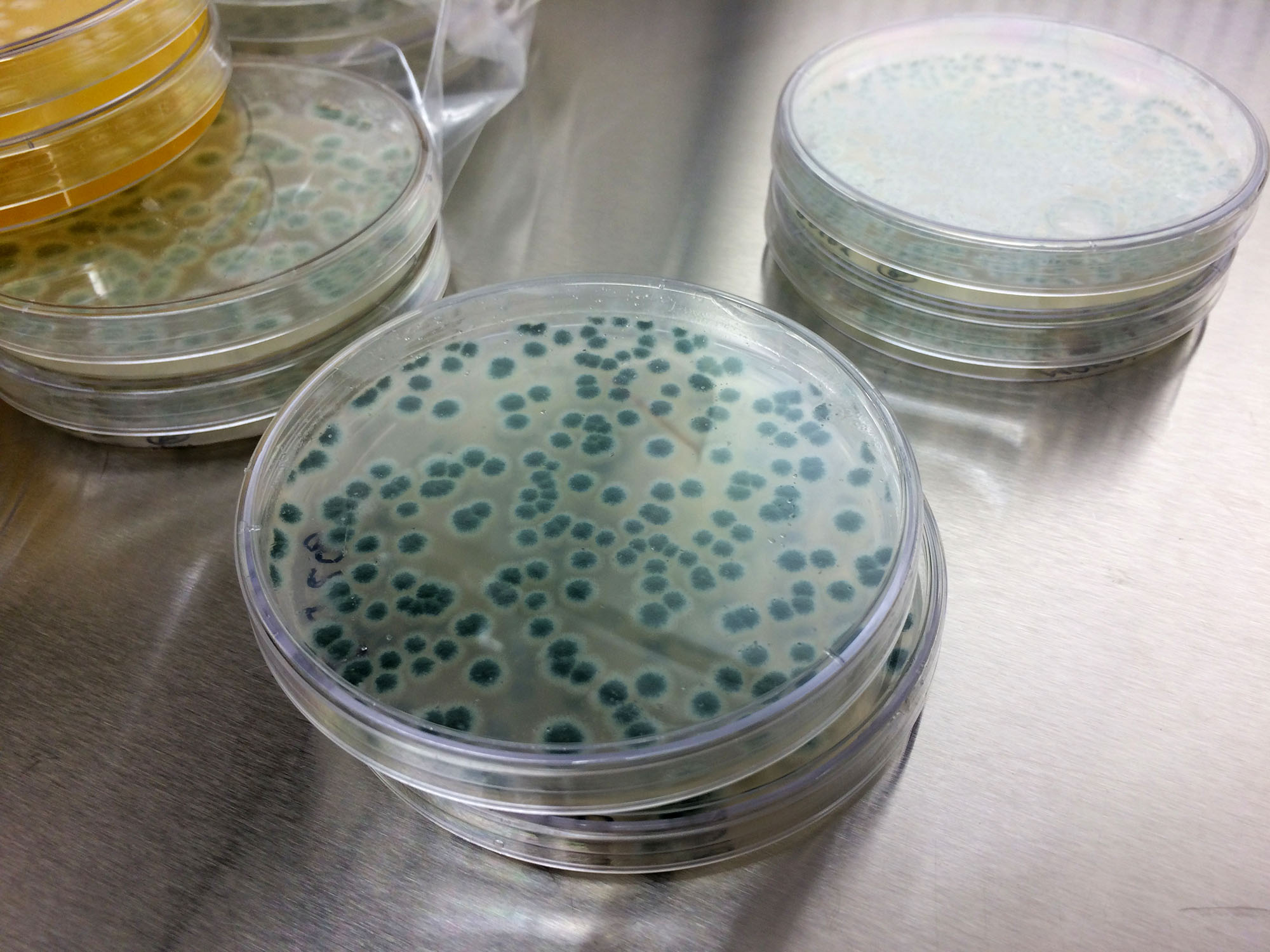

Those early cheese-making peoples spread to Europe, but it wasn't until the Middle Ages that the wild diversity of cheeses we see today started to emerge. In the episode, we trace the emergence of Swiss cheese and French bloomy rind cheeses, like Brie. But here's a curious fact that didn't make it into the show: when Gastropod visited Tufts microbiologist Benjamin Wolfe in his cheese lab, he showed us a petri dish in which he was culturing the microbe used to make Camembert, Penicillium camemberti. And it was a gorgeous blue-green color.

Wolfe explained that according to Camembert: A National Myth, a history of the iconic French cheese written by Pierre Boisard, the original Camembert cheeses in Normandy would have been that same color, their rinds entirely colonized by Wolfe's "green, minty, crazy” microbe. Indeed, in nineteenth-century newspapers, letters, and advertisements, Camembert cheeses are routinely described as green, green-blue, or greenish-grey. The pure white Camembert we know and love today did not become the norm until the 1920s and 30s. What happened, according to Wolfe, is that if you grow the wild microbe "in a very lush environment, like cheese is, it eventually starts to mutate. And along the way, these white mutants that look like the thing we think of as Camembert popped up.”

In his book, Boisard attributes the rapid rise of the white mutant to human selection, arguing that Louis Pasteur's discoveries in germ theory at the start of the twentieth-century led to a prejudice against the original "moldy"-looking green Camembert rinds, and a preference for the more hygienic-seeming pure white ones. Camembert's green origins have since been almost entirely forgotten, even by the most traditional cheese-makers.

Penicillium camemberti growing in a petri dish in Ben Wolfe's lab. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Listen to this week’s episode of Gastropod for much more on the secret history and science of cheese, including how early cheese bureaucracy led to the development of writing, what studying microbes in cheese rinds can tell us about microbial ecology in our guts, and why in the world American cheese is dyed orange. (Hint: the color was originally seen as a sign of high quality.) Plus, Gastropod will help you put together the world's most interesting cheese plate to wow guests at your next dinner party. Listen here for more!

Heather Paxson is a professor of anthropology at MIT, as well as the author of an excellent book, The Life of Cheese, all about the new wave of American artisanal cheese-makers.

Rind microbes from a Colston Bassett Stilton. Photograph courtesy of Benjamin E. Wolfe.

In the episode, Heather Paxson describes the struggles she and her colleagues went through as part of a committee responsible for writing this American Academy of Microbiology FAQ on microbes and cheese, "Microbes Make the Cheese," published in February 2015 and available as a free PDF here.

Paul Kindstedt is a professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of Vermont, where he studies the chemistry, biochemistry, structure, and function of cheese. His book, Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, came out in 2012.

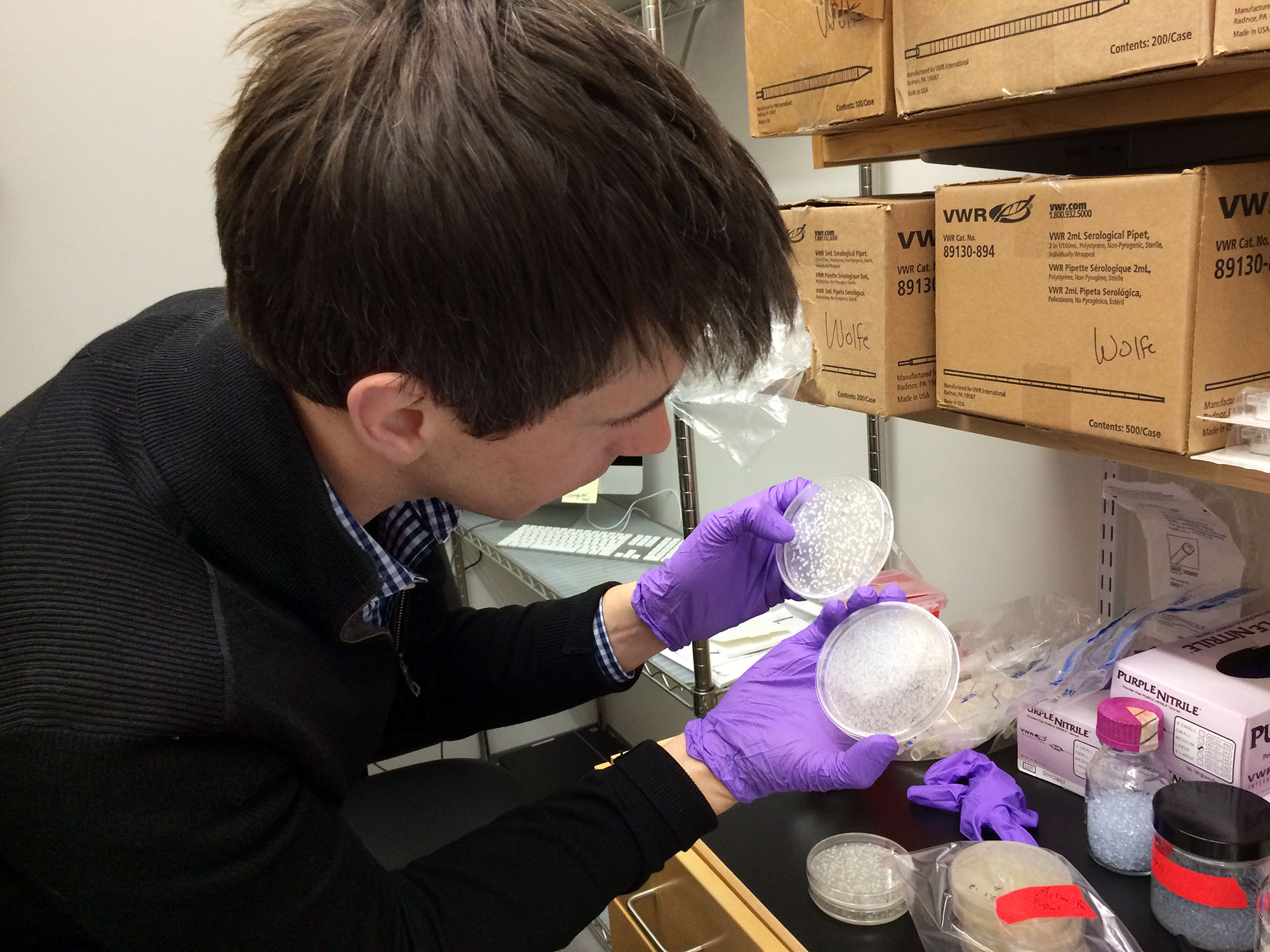

At his lab at Tufts University, microbiologist Benjamin Wolfe studies how microbes from food (mostly cheese!) interact, in order to tease out the ecological and evolutionary forces that shape microbial diversity. He is co-founder of MicrobialFoods.org, an online publication exploring the science of fermented foods.

Ben Wolfe examining his in-vitro cheeses for signs of life. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

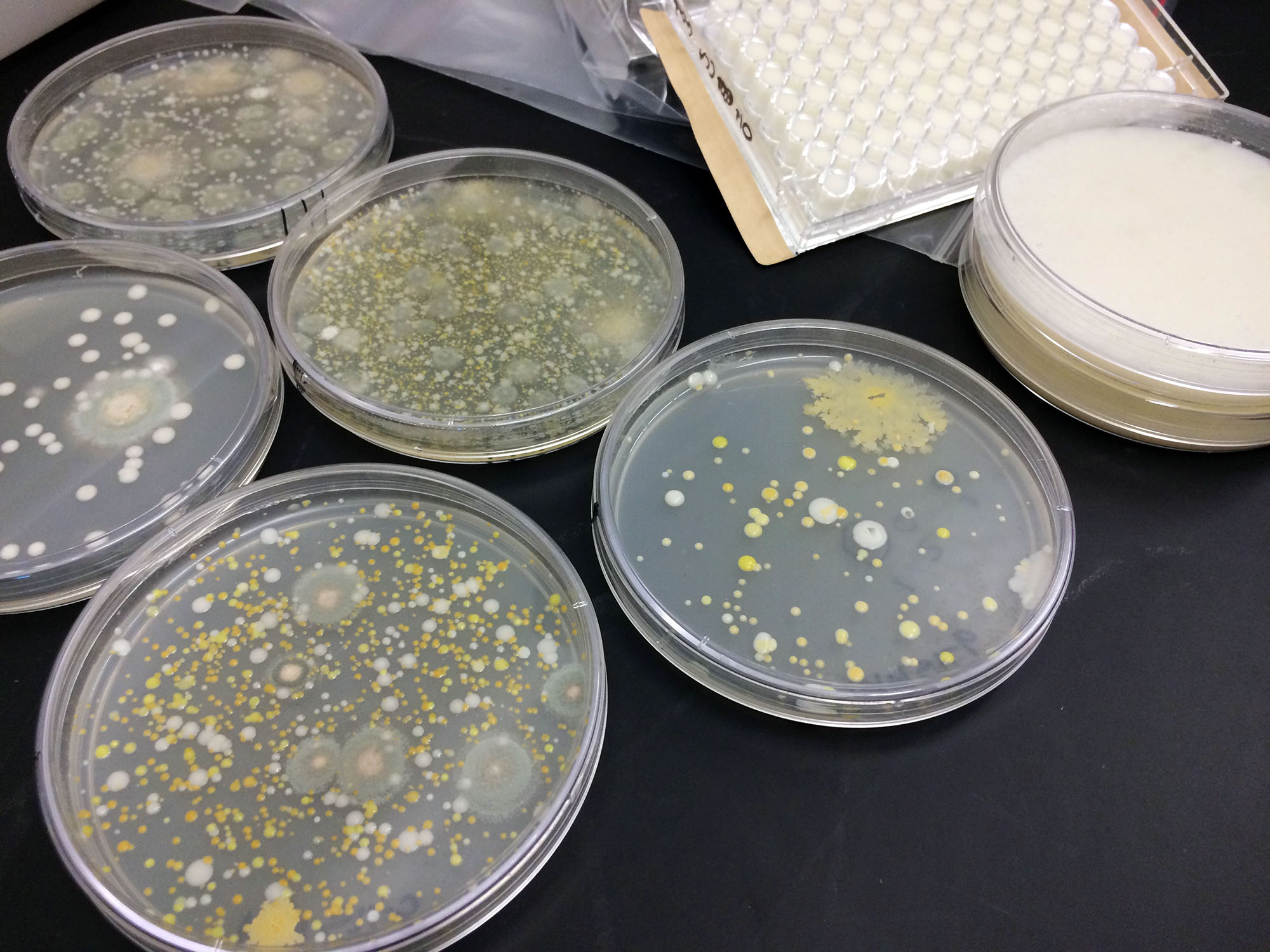

In-vitro cheese rind communities in Ben Wolfe's lab. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

This paper, published in the journal Cell in July 2014, was co-authored by Benjamin Wolfe, Julie E. Button, Marcela Santarelli, and Rachel J. Dutton. The team surveyed 137 European and North American cheeses to assess microbial diversity, with some fascinating results. At the time, Wolfe was working in Rachel Dutton's lab at Harvard's FAS Center for Systems Biology. A Gastropod listener and current post-doc in Dutton's lab, Kevin Bonham, recently wrote a three-part essay at Scientific American that goes into detail about the process for DNA-sequencing a cheese rind, and how to turn that data into useful information.

You may have noticed that some eaters scorn the rinds of cheeses, from the soft fuzzy white carpet that envelops brie to the tougher edge of an aged cheddar, while others tuck right into them. Which approach is correct? The answer depends on what kind of rind it is—as well as your own comfort level with microbes.

Some rinds today are covered with wax, and others, such as England’s Montgomery Cheddar, are surrounded by cloth, neither of which are edible. But for all the rest, the rind is what microbiologists such as Ben Wolfe call a "biofilm"—an entire ecosystem of microbes that colonize the cheese surface, gluing themselves together. Historically, the rind creates a method of preservation, a surface “to keep [the cheese] from being damaged and make it easy to transport. So people just let these rinds develop.” These microbial rinds are perfectly safe for consumption, though they have a different, sometimes stronger, taste than the cheese itself. So: Eat the rind or not? Heather Paxson, who unhesitatingly ate the rind on a St. Nectaire during an afternoon of cheese-tasting with Gastropod, says “It’s purely a matter of taste.”

As we explain in the episode, Ben Wolfe has become something of a "cheese doctor," with cheese-makers sending him their "Frankencheeses" in the mail, in order to figure out what went wrong. Meanwhile, listener "Moldy in Avignon" sent us an email with the subject "Gross Cheese Mystery," and a photograph of really, really old cheeses for sale in the Avignon market. We consulted with Ben, who shared his own photos of brown, nasty-looking French cheeses for sale at the Slow Food Festival in Bra, Italy. Apparently, these kinds of super-aged cheeses are meant for eating, though the cheese seller in this short video explains they are hard to find these days and much less popular than they used to be.

The brown dust is actually microscopic cheese mites: Wolfe calls them the "gophers" of the cheese world, as they eat into the rind, aerating it as well as increasing the surface area available for microbial colonization (and thus flavor development). They're common in cheese aging, although in the U.S. they're usually regarded as a pest, and cheeses are carefully brushed to remove them. Here's footage of a cheese mite munching on microbial hyphae, filmed at the Dutton lab.

Very old cheeses (aged for up to five years) covered in craggly molds and a fine dust of cheese mites. (Left) Photographed by Ben Wolfe for sale at the Slow Food Festival in Bra, Italy. (Right) As photographed by listener "Moldy in Avignon."

This episode wouldn't have been nearly as much fun without all your cheese stories: thanks to all of you who wrote or called in, and particularly to Elana Lubin, Roz Cummins, Emily Lo Gibson, Mike Simonovich, Jenny Morber, Etta Devine, Tasha from the Boston area, and Doug from Perth. We sampled audio from Alex Crowley's Wallace & Gromit "The Cheesesnatcher" claymation, as well as a 1986 Velveeta ad, a 1958 Kraft ad, and a "Time for Timer" Saturday morning cartoon PSA from the 1970s.

For a transcript of the show, please click here. Please note that the transcript is provided as a courtesy and may contain errors.