Gastropod looks at food through the lens of science and history.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Research into the composition, function, and importance of the galaxy of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that, when we’re healthy, live in symbiotic balance in and on us has become one of the fastest moving and most intriguing fields of scientific study. But it turns out that plants have a microbiome too—and it’s just as important and exciting as ours.

In this episode of Gastropod, we look at the brand new science that experts think will lead to a “Microbe Revolution” in agriculture, as well as the history of both probiotics for soils and agricultural revolutions. And we do it all in the context of the crop that Bill Gates has called “the world’s most interesting vegetable”: the cassava.

Isabel Ceballos and Alia Rodriguez surveying the cassava field in Colombia. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

Isabel Ceballos and Alia Rodriguez surveying the cassava field in Colombia. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

We now know that we humans rely on bacteria in our gut to help us digest and synthesize a variety of nutrients in our food, including vitamins B and K. There’s a growing body of evidence that the different microbial communities we host—in our guts, on our skin, in our mouths, and deep inside our bellybuttons—help protect us against disease and may even play a role in regulating mental health.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, plants, including all the ones that we rely on to provide grains, vegetables, and fruit for our tables, have an equally tight relationship with microbes. And, as in humans, the symbiotic partnership between a plant and the microbes that live on its leaves and roots and in the soil around it is utterly essential to the plant’s continued existence and health. Indeed, the very plant-ness of plants—their photosynthetic ability to harness light and transform it into food—comes from an ancient microbe that plants came to depend on so closely that they incorporated it into their own cells, transforming it into what we now know as a chloroplast.

Mycorrhizal fungi growing on a petri dish in Alia Rodriguez' lab. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

Mycorrhizal fungi growing on a petri dish in Alia Rodriguez' lab. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

But, despite its importance to their (and thus our) survival, the plant microbiome is perhaps even less well understood than its human equivalent. The main way in which scientists study such tiny creatures is by growing colonies of a particular microbe on a petri dish in a lab. But researchers estimate that only about 1 percent, the tiniest sliver of the plant world’s microbial citizens, can be cultured that way.

High-tech tools such as metagenomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics help researchers take a snapshot of the genetic diversity of life in a given bit of soil. But it’s still incredibly difficult to tease out exactly which bacteria or fungus performs what function for a given plant. Janet Jansson, whose lab at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is studying the role of soil microorganisms in the cycling of carbon, calls this great unknown “the earth’s dark matter.” She’s part of a new venture called the Earth Microbiome Project, an international collaboration of scientists working to understand microbial communities in soils all around the world.

While researchers scramble to map and analyze the plant and soil microbiomes, companies have sensed that there’s money to be made. When it comes to the human microbiome, processed food giants have started adding probiotics and prebiotics to everything from frozen yogurt to coconut water. In the field, scientists, small biotech companies, and agricultural behemoths such as Monsanto are all racing to develop probiotics for plants: learning from bacteria and fungi to develop supplements that can help crops grow better, using less fertilizer and pesticide, even in challenging environmental conditions.

Mycorrhizal fungi. Photo courtesy of Ian Sanders.

Mycorrhizal fungi. Photo courtesy of Ian Sanders.

In this episode, Gastropod hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley focus on one particular kind of microbe: mycorrhizal fungi. These are ancient fungi that are believed to have lived on plant roots ever since plants first moved onto land, and they still co-exist with and support 80 percent of all plant species on the planet. We meet British scientist Ian Sanders, whose career has been devoted to studying mycorrhizal fungi genetics. Sanders’ latest big idea is that, by breeding better mycorrhizal fungi, he can help plants grow more food. He’s been working with agronomist Alia Rodriguez to test this theory in the cassava fields of Colombia, and we join him to find out his astonishing, as yet unpublished, results. Can the Microbe Revolution live up to its promises, out of the lab and in the field?

Ian Sanders in Colombia. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

Ian Sanders in Colombia. Photo by Cynthia Graber.

Along the way, we discuss other research into plant microbes, some of which has already been commercialized. For example, Rusty Rodriguez, head of a company called Adaptive Symbiotic Technologies, has scoured extreme environments to find fungi that can help plants survive heat, cold, drought, and floods. During trials, AST’s new product, BioEnsure, which was released onto the market this fall, enabled crops planted during the 2012 drought in the American Midwest to produce 85 percent more food than untreated ones.

With early results like these, microbes are being called the next big thing in agriculture. There’s plenty of hype: Monsanto’s BioAg Alliance claims to be “rewriting agricultural history,” the American Academy of Microbiology recently issued a report titled “How Microbes Can Help Feed the World,” and even normally sober scientists have declared that this research may well “precipitate the second Green Revolution.”

But the first Green Revolution has plenty of critics, and the process of translating promising science into food on tables is never without its challenges. Listen in to this episode of Gastropod for the scoop on the history and potential impact of the Microbe Revolution.

This episode, we owe a great deal of thanks first and foremost to Michael Pollan and Malia Wollan, who head the UC Berkeley-11th Hour Food and Farming Fellowship. The funding from this fellowship supported Cynthia's reporting in Latin America—and the fellowship also happens to be where Cynthia and Nicky first met. Thanks are also due to Ian Sanders and Alia Rodriguez, who let Cynthia follow them in the field in Colombia, as well as Rusty Rodriguez, Janet Jansson, Kate Scow, and the dozens of scientists at universities and in various companies who answered Cynthia's questions.

Below are links to some of the articles, people, and foods that we mention in the episode.

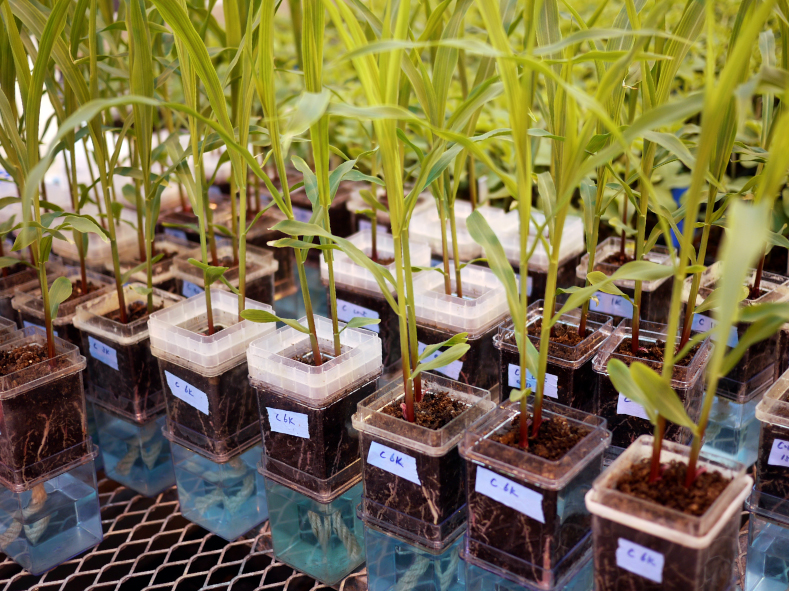

Rusty Rodriguez's Seattle greenhouse. Photo by Cynthia Graber. Rusty Rodriguez kindly provided the image accompanying our Soundcloud file.

Rusty Rodriguez's Seattle greenhouse. Photo by Cynthia Graber. Rusty Rodriguez kindly provided the image accompanying our Soundcloud file.

Cynthia created an entire notebook of scientific research on the agricultural microbiome (you can email [email protected] if you'd like information on even more scientific studies), but here are links to two of Ian Sanders and Alia Rodriguez's key papers related to this experiment: their article on the increase in cassava yields by applying a commercial brand of mycorrhizal fungi to the roots can be read here, and here's the paper where Ian's team at the Lausanne lab demonstrates that mycorrhizal fungi do, in fact, have sex.

Cynthia's research for this episode of Gastropod was first published as an in-depth story at PBS's NovaNext. Read her article for many more fascinating details about the history of microbes and farming, as well as a look at why agriculturals microbes may be particularly crucial in a climate-changed future.

This 2013 report came out of a two-day meeting in DC, organized by the American Society for Microbiology, and it's packed with information about the relationships between plants and microbes, and what this means for the future of food.

Every year for the past three years, Agrow has published a special issue on microbes. Their 2014 issue was called "Crop protection industry upbeat on biopesticides." It takes a minute to log into the site (for free), but it's worth it to get a look at the commercial sector's activities in this realm.

Bubble tea, via.

Bubble tea, via.

As you can read in this photo essay, Bill Gates considers cassava the "stud of the plant world." We think it's fascinating, too, and we were delighted to taste cassava in its many forms in and around Cynthia's home in Somerville, Massachusetts.

You can often find cassava in restaurants going by its alias of yuca, either fried or boiled. In Brazil, cassava is known as manioc (mandioca in Portuguese), and it's also eaten boiled or fried. It can also be found as a thickener in soup, and it is dried and ground into a flour that is pan-fried with spices to create a crunchy topping called farofa.

Probably the best-known version of cassava in the U.S. is tapioca—a third alias for this fascinating vegetable. Our cassava crawl included visits to a Peruvian restaurant, a Brazilian one, and a cafe that sells bubble tea (full of tapioca pearls). Let us know your favorite version of cassava in the comments below!

The Green Revolution is the name given to a combination of enormous advances in plant breeding and the American-led export of a high-input, high-technology form of agriculture to less developed countries, such as India, during the 1950s and '60s. Its supporters credit the Green Revolution with saving a billion lives from hunger, and its architect, plant scientist Norman Borlaug, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Its critics claim the Green Revolution's yield gains were inflated, its technocentric focus ignored the deeper inequalities underlying hunger, and its reliance on fertilizer, irrigation, and expensive hybrid seeds damaged both the livelihoods of small farmers and the environment. It's a fascinating and controversial historical debate, tied into larger geopolitical issues (for instance, the U.S. wanted to keep socialist India from aligning itself with the Communists during the Cold War), and it's well worth trying to understand its successes and failures, in the hope that we can avoid making the same mistakes again.

Where to start, though? On the skeptical side, author and activist Raj Patel wrote a recent post titled "How to Be Curious about the Green Revolution," which poses some important questions. He also authored a recent academic paper called "The Long Green Revolution," available here. The most recent book on the topic is titled The Hungry World, by historian Nick Cullather. In its paper, "Green Revolution: Curse or Blessing?," the International Food Policy Research Institute provides a slightly more positive analysis of the benefits and problems associated with the Green Revolution, as does this Food & Agriculture Organization technical background document. If you know of any particularly interesting reading on the topic, let us know.

For a transcript of the show, please click here. Please note that the transcript is provided as a courtesy and may contain errors.