Gastropod looks at food through the lens of science and history.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

Co-hosts Cynthia Graber and Nicola Twilley serve up a brand new episode every two weeks.

"Koreans traditionally have kimchi at all three meals: breakfast, lunch, and dinner," food ethnographer Kevin Kim told Gastropod. Some scholars say the true origin of kimchi lies in China and Chinese fermented vegetables, and others point out that the chili pepper that gives most kimchi its distinctive spiciness is a New World ingredient. But kimchi is so quintessentially Korean that, according to historian Michael Pettid, as early as 2,000 years ago, Chinese records remarked on the special fondness that the people living in the Korean peninsula had for fermented vegetables.

More recently, Kim told Gastropod, Korean politicians have invested heavily in supporting kimchi producers, kimchi science, and kimchi marketing campaigns as a "soft power" strategy to promote the country and its culture overseas. Their efforts have paid off. As Lauryn Chun, creator of Mother-In-Law's Kimchi and author of The Kimchi Cookbook, can attest, today, kimchi is found on grocery store shelves across America, where it's beloved for its salty, spicy, garlicky crunch, as well as its probiotic potential. Some credit the kimchi taco, which chef Roy Choi first served from his Los Angeles-based Kogi food truck in 2008, with inspiring kimchi's cult status among foodies, but kimchi has since gone mainstream: in the past decade, the condiment has begun popping up on chain restaurant menus from TGI Fridays to California Pizza Kitchen.

The microbial diversity of Cynthia's kimchi, as plated by Esther Miller.

The microbial diversity of Cynthia's kimchi, as plated by Esther Miller.

Surprisingly, it turns out that all that deliciousness is dependent on a set of microbes—specifically, lactic acid bacteria—that are extremely hard to find on cabbages and in the field. "One thing that I find really fascinating about kimchi compared to other fermented foods is that, unlike cheese or salami or yogurt, where you use starter cultures—these microbes that you buy—kimchi is not inoculated," said Tufts University researcher Benjamin Wolfe, who also serves as Gastropod's in-house microbiologist. This made him wonder: if these bacteria don't really like to hang out on cabbage leaves, and we don't intentionally add them to our ferments, where do the microbes that turn cabbage into kimchi come from?

To investigate, we team up on an experiment of our own, making multiple large jars of kimchi in an attempt to discover whether the microbes in the final ferment differ depending on the farm where the cabbage was grown. Listen now to find out the results of the experiment—and hear stories of insect-smushing, kimchi block parties, and the kimchi that was specially designed for space!

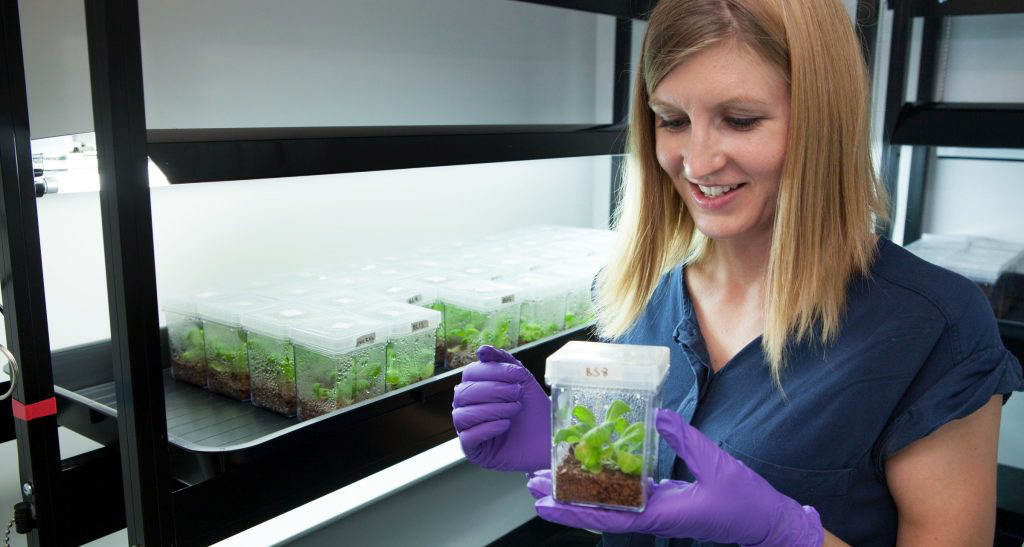

Esther Miller with her sterile cabbages. Photo by Kevin White.

Esther Miller with her sterile cabbages. Photo by Kevin White.

You can find our microbiologist-in-residence Ben Wolfe at Tufts University, where he heads the Wolfe Lab, as well as on Twitter @lupolabs. He starred in our kombucha episode, as well as our episode all about cheese. Graduate student Esther Miller joined the Wolfe Lab in 2015, and her research focuses on microbial dynamics in the cabbage phyllosphere.

Cynthia's microbial terroir kimchi experiment in the lab.

Kevin Kim is a doctoral student at the University of Maryland, in the department of American Studies. His focus on food ethnography includes research on "kimchi diplomacy."

Lauryn Chun is the founder of Mother-In-Law's Kimchi, and author of The Kimchi Cookbook.

Historian Michael Pettid's book, Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History, is a definitive guide to kimchi's origins and traditional cultural significance.

Click here for a transcript of the show. Please note that the transcript is provided as a courtesy and may contain errors